Engineer’s Notes

Engineer’s Notes on 3D audio engineering of “The Tale of Genji, Symphonic Fantasy”

TThe recording of The Tale of Genji: Symphonic Fantasy performed at Izumi hall in Osaka was my last work with Mr. Tomita.

This piece is a huge concerto that contains five soloists of Japanese traditional instruments and a storyteller in Kyoto dialect. For the performance a sound reinforcement system was a necessity as the storyteller’s natural voice wouldn’t have been audible with the sound of the orchestra. In addition, there are four surround-sound channels of a musique concrète kind of piece performed on synthesizer played by Mr. Tomita himself. This was played together with the orchestra to develop and enhance the musical world the composer sought to create. The piece unequivocally exceeded the typical standard for musical composition, and the audience was captivated and mesmerized while listening to the performance.

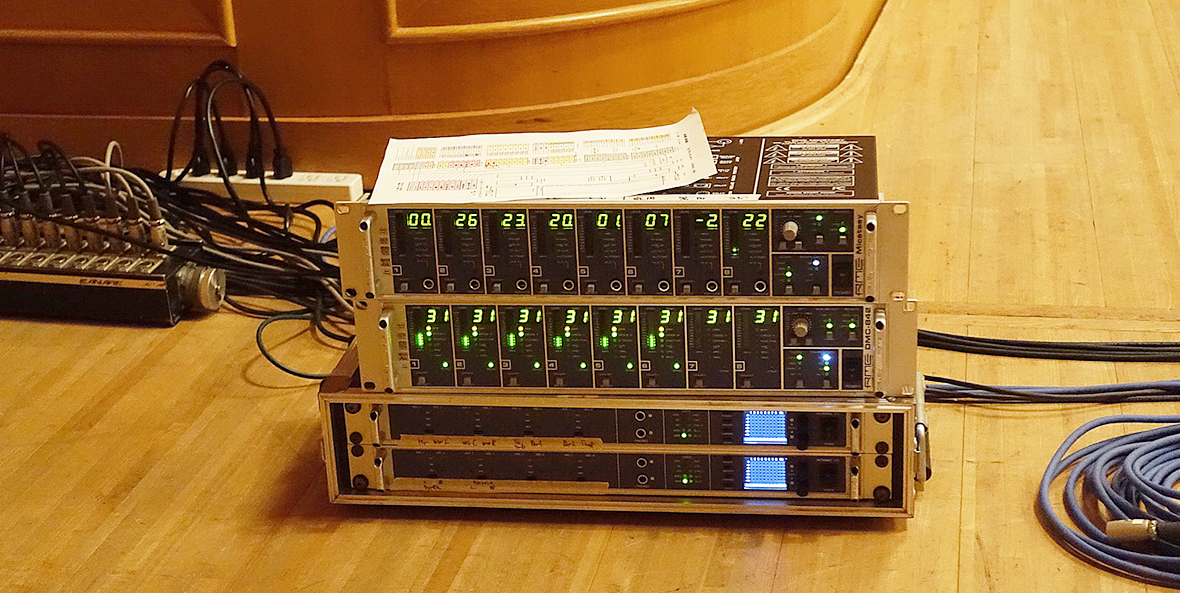

This work was recorded in April 2015, five years prior to this writing, and was done by using 3D audio technology that was becoming more developed at the time. 3D audio happened to be a perfect fit to express the scale of the piece. Although the recording was made five years ago, I aimed to record with the most current technology possible in order to prevent the work from becoming obsolete. In order to accomplish this, I applied digital microphones to the main parts of the microphone arrangement and pressed ahead with high-resolution recording. With the evolution of digital audio workstation music recording software—the industry-wide acronym for this technology is DAW--and the opportunity for conversion to Blu-ray format, I took this occasion to remix the entire project. Ultimately, I was relieved and grateful that the sound quality became more full-bodied and lush through the post-production process.

While the recording methods used are also relevant to normal stereo recording, keeping the balance between the direct instrument sounds and the rich room tone of the hall is crucial when recording acoustic music such as classical music. Direct instrument sounds have more intelligibility than the room tone, and mediating the balance of both is absolutely important.

That being said, there are limits in stereo recording for achieving an ideal balance of sound. This challenge is an inevitable phenomenon due to the fact that in a stereo environment both music and physical reverberation are combined into a pair of stereo speakers.

Alternatively, the solution lies in 3D audio technology. This medium allows the sound elements to be scattered or dispersed to multiple speakers in 3D audio, and in doing so the intelligibility of the instrument sounds and tone of the room can coexist, engulfing listeners in the atmosphere and breadth of sound that they would be able to hear in the actual concert hall. Broadly speaking, the music won’t be buried into ambience when using 3D audio simply because the speakers that play the music are separated from the speakers that play the room tone.

To achieve this, two kinds of microphones--main microphones for instruments and ambient microphones for the room sound--were used in the recording. The technical terms for these two elements are objective presence and field presence. Both of these elements are fine-tuned and optimized then combined in the playback field. Although the process may sound complicated, essentially what we do is use the right microphones in the right places to record instruments and the room tone.

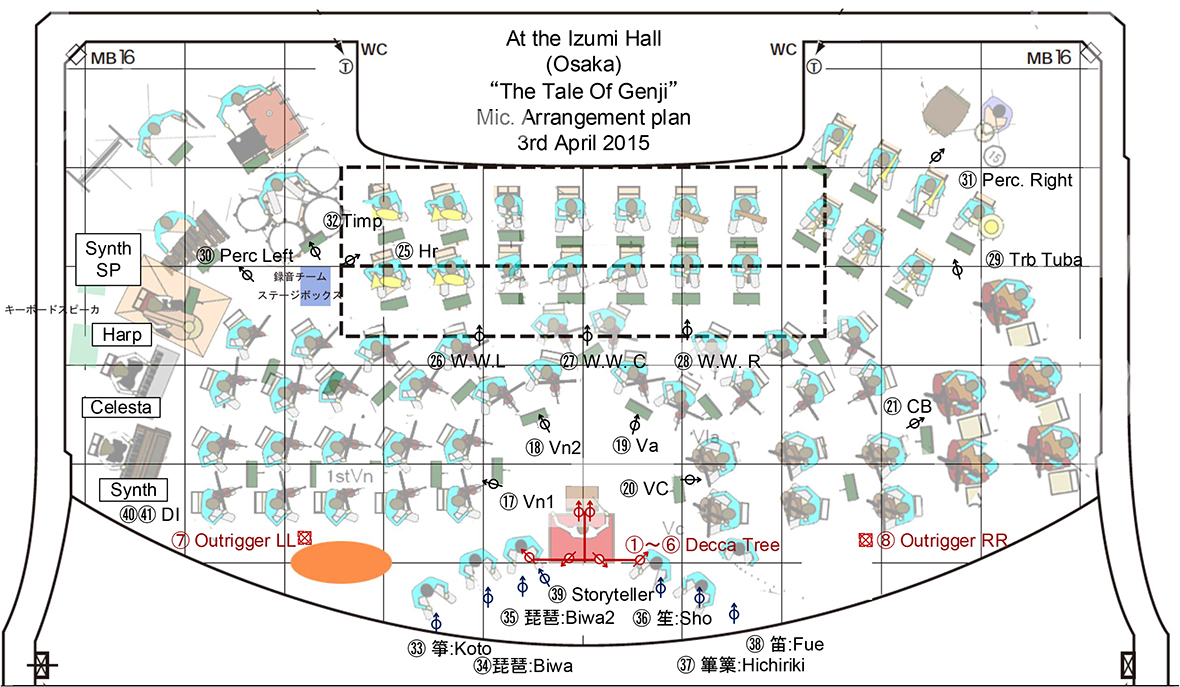

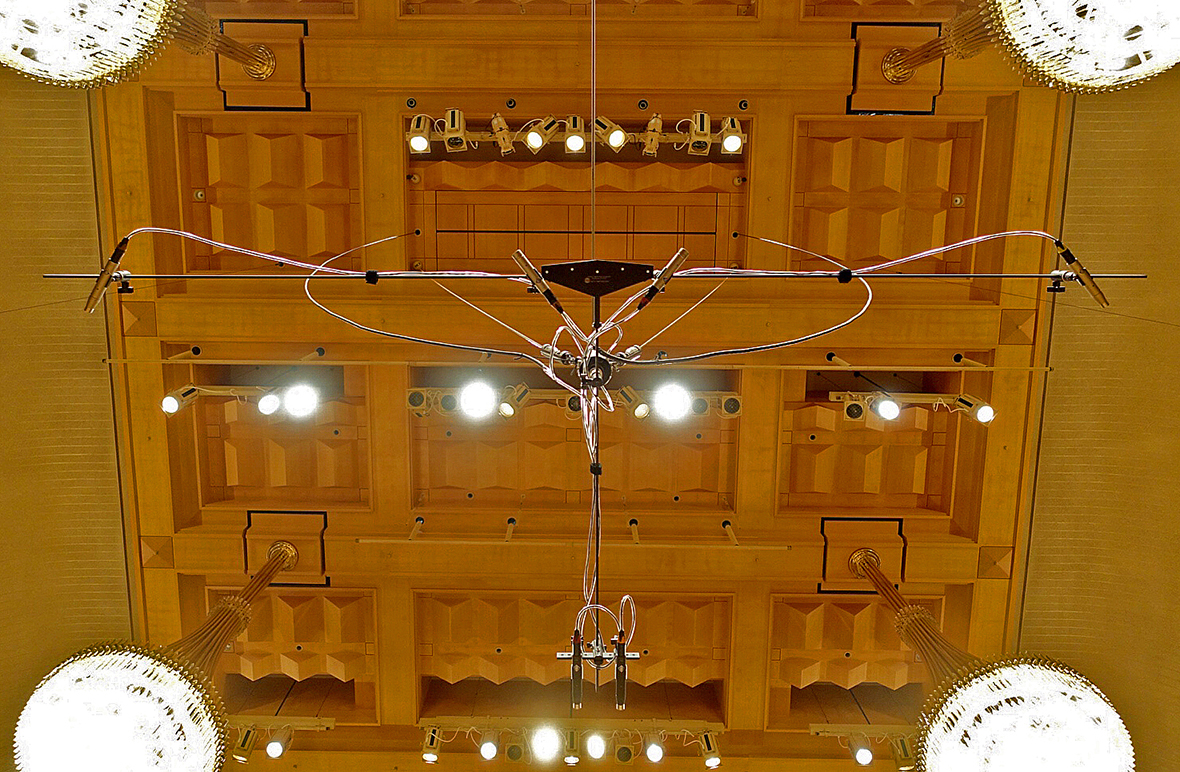

I usually prefer using the Decca Tree, developed by Decca Records, for three microphones for the Left, Center, and Right channels. You can see it on figure 1. Originally, three omnidirectional microphones are attached to the tips of the reversed t-shaped bar of the Decca Tree, but I modified the traditional configuration and swapped the traditional omnidirectional center microphone with paired microphones.

I chose to make this alteration because using physically-divided paired microphones in the center channel connected to Left and Right cast speakers provides more natural breadth than a single microphone electronically divided to Left and Right channels. Furthermore, whenever I am working with 5.1 surround sound or 3D audio that contains a center speaker, I prefer to use either one or two microphones and connect them both to hard center in the audio mix.

And as you can see in picture 1, the paired stereo microphones are facing backward from the center of the Decca Tree. These are cardioid microphones and used for Ls and Rs channels for surround sound. The microphones are set at 90 degree angles and 30 centimeters apart. The center microphones are attached to the same bar that also has microphones for the Left and Right channels, but it may be better to set them to extend forward towards the opposite side of the center microphonesI chose to use those microphones for the specific purpose of capturing horizontal breadth.

As an engineer, I feel like I have an obligation to clear up some misunderstandings about speaker placement. The recommended speaker angle for Ls and Rs in the case of 5.1 surround sound is ±110°. From the perspective of the listener this would be more of a side position rather than a rear position.

In terms of the music listening experience, the purpose of surround speakers is to generate a feeling of spaciousness and envelopment from both the left and the right when the listener is in a forward-facing position. However, if the speakers are placed at ±135° in the rear position,, the sense of sound envelopment will decrease and the direct sound leaking from behind will detract from the listening experience.

Obviously, ±110° placement wouldn’t be a fit for film soundtracks that inherently require sound from behind in order to experience the true impact of sound effects. That being said, if you have a 5.1 surround system with speakers placed behind, try placing them closer to sideways when you listen to music. I think you will notice that your impression of the music will change significantly.

Returning back to the actual recording method of this orchestral work, two microphones for the outrigger (LL and RR in figure 1) were placed on both sides of the Decca Tree.

Etymologically, an outrigger is a beam or framework projecting from or over the side of a boat or yacht to stabilize the floating structure. In the realm of audio engineering it is called an outrigger because it projects toward both sides from the main microphone. The purpose of using this method is to capture the spread of all of the instruments across the stage as well as to improve the breadth and quality of the recording. In regular 3D audio mixing, LL and RR channels will be mixed as L and R channels, but in the 9.1 surround system they can be connected to wL and wR speakers (placed outside of the main speakers) to capture and manifest the rich span of the orchestra.

Nonetheless, I connected these two microphones to HL and HR channels for this project. They were connected to high layer speakers. In recent recordings, I sometimes use a double-deck Decca Tree connected to vertically-aligned speakers to give the instruments a three-dimensional character in a longitudinal direction. This method serves to improve the presence of the instruments.

Although this application in some ways deviates from the intended purpose of the outrigger, the distance from the main microphone was similar to the application of the double Decca Tree, and I felt comfortable attempting this method and connecting them to the upper speakers. It still sounded different from Double Decca microphone placement technique, but I decided to employ this method since it helped to improve the sonic texture of the orchestra.

Picture 2 is the image of the Decca Tree taken from behind at a diagonal angle. The microphone suspended on the right side is the outrigger. Speaking of the ambient microphones employed for capturing room tone, we hung a two-square-meter “X” figured microphone array that has four omnidirectional microphones at each end for the upper layer. It was suspended approximately 10 meters both behind and above the main microphones.

We call this array system omni-cross.

For ambient microphones used in the lower layer, I usually set them up to encompass the auditorium in order to capture applause and cheers from the audience, but we had to abandon this method because it was almost impossible to place microphones throughout the auditorium due to the fire-safety regulations. Instead, we configured a cuboid-shaped array by hanging four omnidirectional microphones three meters below each end of the omni-cross. Another term for this particular arrangement is omni-cube since all of the microphones are omnidirectional (Picture 3).

Because the lower microphone of the omni-cube was positioned more than 10 meters above the audience, I was concerned that this arrangement would have too small of a physical space between the upper and lower microphones. My apprehension was that this would affect the aural perspective of the applause and cheering from the audience and that it might give the impression that it was floating in the air. However, when I actually listened to it I was satisfied with the sound. Actually, it would have been ideal to playback close-range applause from the lower speakers to lower the spatial gravity point. Doing so would recreate the natural atmosphere of the concert hall space. But for this Blu-ray disc, since the applause is only heard at the end, there was no need for the perspective expression to be employed.

I minimized the use of spot microphones for the orchestra, and used them moderately for soloists of the Japanese traditional instruments to add some perspective. At any rate, the priority when I was mixing was to express a grand sense of unity among the elements of the orchestra. This being said, the challenging part was the storyteller. The narrative passages were relatively loud in the sound reinforcement system during the actual performance, and because of this the echo of the speaking voice was recorded. The volume had to be mixed at a certain level to maintain its intelligibility. Although it is quite easy to bring up the level of the storyteller, the danger in this method is that, if mixed inappropriately, the final product can end up sounding equivalent to a voice speaking over background music. The effect would be something akin to a broadcast radio play. To avoid this outcome, I mixed the audio with extreme caution to keep the best possible intelligibility while blending it into the sonic world of The Tale of Genji: Symphonic Fantasy at the same time.

A special method was used for the musique concrète component performed by Mr. Tomita. Instead of replacing it with the original sound source, I maximized the sound played through the sound reinforcement system in the hall and remixed the original sound source from 4 channels to 11.1 channels for better consistency. I repeatedly listened to the mix to find the ideal balance without jeopardizing the concept of the original 4-channel mix by the composer. I completed my work for the “Spirit” section just like that. Although this section is one of the highlights of the piece, I personally feel that the most impressive part is the performance in the section spanning “Elegy Of Lady Murasaki” through "In The Vale Of Tears" played with myochin hibashi, which are a type of metal chopsticks. The unique sound of this instrument was in the musique concrète part and was performed by 10 members of the orchestra dispersed in different areas on the stage. It sounded something like diamond dust shining in the underworld and created an ethereal atmosphere when combined with Sakata’s melodic voice.

In my opinion, this piece is unquestionably the masterpiece of the great composer Isao Tomita.

I remember his response when I first played the mix in front of him. He said, “A lot of my work had been written specifically for studio recording, and I don’t have that many pieces designed for live performances. Two previously released versions of The Tale of Genji: Symphonic Fantasy were both based on recordings and weren’t optimized for future generations to perform. It was my dream to hand down this work as a piece that could be replayed by anyone.”

Considering the fact that Mr. Tomita himself had attended practice sessions for the concert to give detailed instructions about the performance and accepted the edits and the provisional mix five years ago, it’s safe to say that this is the genuine performance reference and sound source for The Tale of Genji: Symphonic Fantasy. While it may be difficult for us to imagine this piece being replayed in the future due to its scale, I am sure that the late Mr. Tomita, who now resides in heaven, would be pleased to know that this audio recording could serve as inspiration for future performances.

I feel genuinely blessed to have been involved in this production as an engineer. I feel that this recording was made possible by fortunate circumstances, bringing together everyone who was involved, and I am filled with gratitude for everyone who participated in the project.

Hideo Irimajiri

WOWOW Inc.

Hideo Irimajiri was born in 1956 and graduated from Kyushu Institute of Design in 1979 and its graduate school in 1981. He earned a PhD in Art and Engineering in 2013 for research into reverberation. He began working for the Mainichi Broadcasting System Incorporated in 1981. After working in the video engineering, audio engineering, hall engineering, post-production and mastering divisions, he was transferred to WOWOW Incorporated in 2017 and was appointed executive creator at WOWOW in 2020. In 1987 he was involved in the first project to broadcast high school baseball games in surround sound. Since 2005, he has been engaged in researching loudness issues in broadcasting, as well as working towards standardization as a member of ARIB and the Federation of Commercial Broadcasters of Japan. He has worked on recording ever since his student days, with a focus on exploring 4-channel recording and spatial acoustics. Currently, in addition to developing 3D audio technology, he is actively engaged in the production and dissemination of new work. Further, on a personal level, he has worked as a music producer under the pseudonym Jiro Irima and was in charge of the opening theme for the Hanazono High School Rugby team and the PC game Record of Lodoss War.